When Alfred Hitchcock famously said, “The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture,” he wasn’t merely offering a catchy tagline — he was unveiling a master key to the success of his cinematic legacy. Known as the “Master of Suspense,” Hitchcock revolutionized the thriller and horror genres by crafting villains that were far more than mere plot devices. His antagonists were deeply human, disturbingly relatable, and often the very soul of the story.

In this article, we explore how Hitchcock’s villains — especially Norman Bates from Psycho — have become some of the most iconic in film history. We’ll dive into why compelling antagonists matter in storytelling and how Hitchcock used them to transform his films into timeless classics.

The Power of the Villain in Storytelling

In traditional storytelling, the hero’s journey is often front and center. But Hitchcock flipped the formula. He understood that a movie’s success often hinges not on the protagonist’s strength, but on the depth, charisma, and unpredictability of its antagonist. The villain drives the conflict, challenges the hero, and pulls the audience into the moral gray zones.

A flat villain makes a movie forgettable. A complex villain? That’s what keeps audiences up at night — and what keeps them coming back.

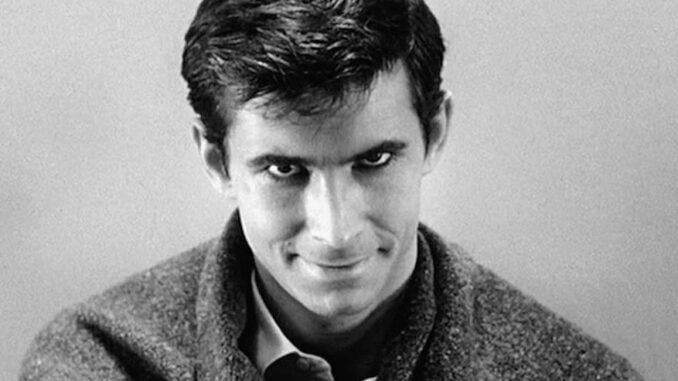

Norman Bates: The Most Human Monster

The perfect embodiment of Hitchcock’s philosophy is Norman Bates, played by Anthony Perkins in Psycho (1960). On the surface, Norman is polite, shy, and endearingly awkward. He seems harmless — even likable. But beneath that innocent smile lies a fractured psyche and a chilling alter ego.

What makes Norman so terrifying isn’t just the murder in the shower — it’s that viewers can relate to him. He’s not a distant monster like Dracula or Frankenstein. He’s the guy next door. He’s a son who loves his mother — maybe too much. Hitchcock masterfully created a character whose madness feels disturbingly real. And that’s what makes him unforgettable.

Psychological Realism: The Hitchcock Signature

Unlike typical horror directors of the era, Hitchcock was less interested in gore and more fascinated by the inner workings of the human mind. He built suspense not through cheap jump scares, but through psychological tension. Villains like Norman Bates, Bruno Anthony in Strangers on a Train, and Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt weren’t evil for the sake of it — they were driven by complex motivations and distorted worldviews.

This psychological realism is why Hitchcock’s villains endure in popular culture. They reflect the darker sides of ourselves — our repressed desires, fears, and guilt.

Villains as Mirrors

One of Hitchcock’s greatest tools was irony. He loved flipping expectations and forcing audiences to confront uncomfortable truths. In Psycho, for instance, the film begins as a story about Marion Crane — and just when we think she’s the heroine, she’s brutally killed. Suddenly, the focus shifts to Norman. By forcing us to follow the “villain,” Hitchcock challenges our moral compass.

He makes us feel for Norman. And then horrifies us with what Norman is capable of.

In doing so, Hitchcock’s villains don’t just drive the story — they become the story.

Hitchcock’s Legacy: The Rise of the Sympathetic Antagonist

Modern cinema owes a great deal to Hitchcock’s approach to villains. Today’s complex antagonists — from Hannibal Lecter to Joker — are spiritual descendants of Norman Bates. These characters aren’t just obstacles for the hero. They are central to the emotional and thematic weight of the narrative.

Without Norman Bates, there might not be a Dexter, a Breaking Bad, or even Gone Girl.

The Craft Behind the Terror

It’s easy to overlook just how revolutionary Hitchcock’s technique was. He used camera angles, lighting, and music not just for aesthetic — but to make the audience feel the villain’s presence. In Psycho, the famous shower scene isn’t gruesome because of what it shows — but because of what it implies. The rapid cuts, screeching violins, and Janet Leigh’s scream create an emotional punch that lingers long after the blood has been cleaned.

And yet, we never see the knife touch the body. That’s pure Hitchcock.

Conclusion: Evil, Made Human

Alfred Hitchcock didn’t just create terrifying villains — he made us understand them. By grounding his antagonists in psychological realism and emotional depth, he forced us to grapple with the shadows in ourselves.

When he said, “The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture,” he wasn’t just giving filmmakers advice. He was pointing to a universal truth about storytelling: that in darkness, we find drama. And in conflict, we find connection.

As long as cinema exists, Hitchcock’s villains — especially Norman Bates — will remain a chilling reminder of how close the line is between normal… and nightmare.